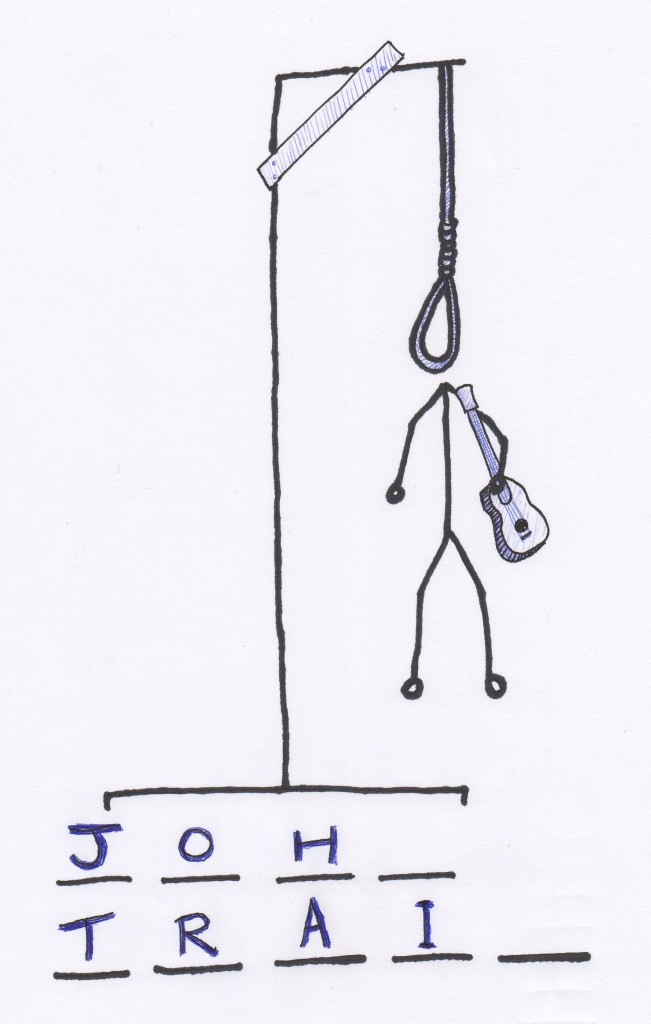

Having followed his dreams and procured a length of solid rope, Joy Division’s vocalist Ian Curtis is now immortalized as the sad boy whose brief life amounted to a self-created death icon. Born and raised in the small city of Macclesfield—situated between hilly pastureland and the grey industrial husk of Manchester in north England—he saw little else to aspire to besides a world-famous tombstone.

Ian never got too far from home—and never for long. Most of his intense rock n’ roll career was nurtured within a clinging arm’s length of his highschool sweetheart, Debbie—whom he married in his teens—and a pint glass’ throw from his childhood home. Music was his only escape into a wider world. By the time he closed the curtain on May 18, 1980 at the age of 23, he had only recorded two full-length albums and a handful of singles. So he was damn sure to make every song count.

Like many boys in the bleak, economically depressed 1970s, Ian Curtis was immersed in the morbid iconography of martyred pop stars. He loved James Dean and Janis Joplin. Among his favorite songs were Jim Morrison’s “The End,” David Bowie’s “Rock n’ Roll Suicide,” and Mott the Hoople’s “All the Young Dudes” (also written by Bowie.) Ian frequently said he didn’t want to live past his twenties, and spent his few years with Joy Division writing songs to an oblivious world about why it was not worth living for.

Joy Division’s droning post-punk minimalism is a fitting compliment to Ian’s mesmerizing, if overly-affected baritone vocals—a voice that seems completely disconnected from the singer’s boyish face, like he was huffing keyboard duster before every song. Curtis’ jerky, robotic dance moves were as disturbing to fans as they were thrilling—and made for a peculiar preview of the epileptic seizures that would wreck his health during his last years alive.

The band’s name is taken from The Doll House, a German novel about a Jewish girl sent to a concentration camp brothel provided for Nazi officers known as “the Joy Division.” Ian’s raw-nerve sensitivity to the jagged edges of a cruel world is evident in their first full-length album, Unknown Pleasures, particularly the bitter distance that grows between two lovers:

Me in my own world, yeah you there beside

The gaps are enormous, we stare from each side

We were strangers for way too long…

Ian met Debbie when he was only sixteen. Their first date was to see David Bowie’s performance of Ziggy Stardust in Manchester. Despite his father’s reservations, Ian sold his guitar to buy a wedding ring for his one true love. He took a job as a civil servant and they bought a house together, though Ian’s rock n’ roll fantasies never wavered.

According to Debbie, her husband was consumed by incorrigible jealousy. She claims that he only proposed to keep other men from showing her too much attention. Ian did tend to freak out a lot, like the time he saw his wife-to-be dancing with one of her young uncles at their engagement party and threw a Bloody Mary in her face. He was constantly worried that Debbie would meet someone else, and refused to let her wear anything remotely sexy out of the house.

Perhaps his fears were simply guilt-projection. He later confided to a friend that he nearly backed out of the wedding because he felt sure that one day he would eventually be unfaithful. Of course, a musician predicting his own philandering is like a hitch-hiker predicting a roadside molestation—it’s bound to happen eventually.

It was decided early on that wives and girlfriends had no place at Joy Division’s shows. A rock star’s main squeeze always gets in the way of tour antics, and Joy Division’s endless pranks—which tended to involve their own shit and piss to an alarming extent—would have undoubtedly put off their lady friends. So would the groupies.

Ian and Debbie’s daughter, Natalie, was born in the spring of 1979 during the recording of Unknown Pleasures. Ian witnessed the birth, but it was a momentary connection for a young man prone to detachment. While Debbie poured her affection onto her newborn baby, Ian’s eyes were fixed on the stars.

Annik Honoré was doing a bit of star-gazing herself, and after seeing Joy Division perform at Nashville Sounds in London, she decided to reach out and grab one of those crazy diamonds. The lovely Belgian writer arranged to do an interview with the band for a fanzine, after which she and Ian remained in contact. Ian was hardly a skirt-sniffing cad, but there was something about this exotic young woman that sparked an inferno inside him. “There was some electricity in the air every time we would see each other,” she said after his death, “every time we looked at each other.”

Annik was everything that Ian’s wife was not: educated, articulate, well-traveled, and unwaveringly self-determined. They would talk for hours about art, literature, and film, her sexy Belgian accent captivating the provincial English singer. After their first kiss at London’s Electric Ballroom, there was no turning back. Time was too short to waste on patience—yet Ian’s conscience was too strong to stave off the guilt.

Curtis tortured himself to death in the chasm between domestic responsibility and the romance of rock stardom. He withdrew from his wife and daughter when at home, spending endless hours alone in his blue room with his notebook and little dog, Candy. His grand mal seizures had also grown progressively worse, usually triggered by performances, though occurring more frequently at home.

Oddly enough, years before he suffered his first seizure in 1978 Ian had worked with a number of epileptics while employed as a Disablement Resettlement Officer, where he witnessed rooms full of pitiful patients wearing helmets and pads. The song “She’s Lost Control” is apparently about one of these unfortunate souls:

And she screamed out kicking on her side and said

I’ve lost control again

And seized up on the floor, I thought she’d die

She said I’ve lost control…

Doctors fumbled in the dark to find a pill that could fix his brain, but effective treatments would not be developed for more than a decade. Too late. The chemical cocktails began to fry Curtis’ circuits, sending him into long bouts of uncommunicative depression. Somehow he managed to take the stage night after night anyway, and in January of 1980 Joy Division embarked on their first—and only—European tour.

Debbie wanted to come along for the sights and adventure, but Ian stoutly refused, leaving her at home with the baby and their dog. Despite Annik’s attempts to walk away from her impossible love, she would join him for six days in Europe. It was to be the longest time they would spend together, and one of the last.

According to Annik, she and Ian never once made love. Aside from her own guilt over an affair with a married father, she says she was a virgin, wary even of Ian’s modest sexual experience. This apprehension, coupled with her lover’s rapidly deteriorating health, ensured that Annik’s nubile body would remain for Ian an unknown pleasure. Their romance would continue in an urgent exchange of letters, but they could never come closer.

“You are the only thing that makes me truly happy at this moment,” Ian wrote, “when I’m with you, when I’m near you, when I think of you…

“I am paying dearly for past mistakes. I never realized how one mistake in my life some four or five years ago would make me feel how I do. I live beyond obligation and responsibility…. I struggle between what I know is right in my own mind and some warped truthfulness as seen through other people’s eyes… I thank God I have my solitude…”

On the night of Ian’s return home, Debbie came home to find her husband pilled-out on the blue room’s floor and stabbing holes into a Bible with a kitchen knife, having already cut himself up a bit. The next day she asked him if he didn’t love her anymore.

“I don’t think I do,” he said.

A few days later Debbie became desperate for answers and tore through Ian’s notebooks. There she found Annik’s name and address. She confronted him, and he admitted infidelity. Debbie decided to get a divorce.

Upon considering the fact that Ian carried pictures of his dog instead of his family, Debbie decided that she was done taking care of little Candy and gave her away as well. She then proceeded to call Ian’s parents and tell them everything. Finally, she called Annik at her office to berate her for being a home-wrecker.

Joy Division continued playing gigs around England and started work on their second album, Closer, but their singer was teetering on the brink. On Good Friday 1980 the band played two shows back to back. Ian worked himself into a spastic frenzy as usual, but fell unconscious at the peak of both sets, bringing the performances to a grinding halt. The drinking, lack of sleep, and flashing stagelights had become more than his electrified neurons could handle.

On Easter Sunday he wrote a suicide note and swallowed a handful of Phenobarbitone. Upon realizing that he had not taken enough to die, he woke his wife to call an ambulance so as to avoid becoming a brain-dead zombie pissing blood all over himself. His failed attempt to play a show the next night resulted in a riot. Ian’s manager found him crouched upstairs afterward, weeping.

Despite Ian’s ragged state, the band decided to go forward with an upcoming American tour, and were set to leave on May 19. Rock n’ roll slows down for no man—“there’s no room for the weak,” as the lyric says.

Ian stayed away from home for a couple of weeks to let things cool off, but on May 17 he returned to pick up some things and say goodbye to his daughter. Debbie found him there that afternoon, and he begged her to call off the divorce. She agreed to spend the night with him and left for a bit, but by the time she got back he had changed his mind again and told her not to come back until he was on his way to the airport. Apparently he had spoken to Annik on the telephone and promised to honor his last letter and end his marriage for sake of true love. She was on her way from a trip to Egypt to see him.

Alone again, Ian pulled out pictures of his wife and daughter, and wrote an impassioned letter begging Debbie for reconciliation. He watched Werner Herzog’s Stroszek, a film about a European artist who cannot decide between two women and so chooses to kill himself. He put Iggy Pop’s The Idiot on the record-player, drank a pot of coffee, and finished off the last of a bottle of whiskey. Then he tied a cord to their old-fashioned clothes rack and hung himself in the kitchen. Debbie found the letter first, then noticed his body. The noose had cut deep into his throat and he had practically sunk to his knees.

Ian Curtis was pronounced dead on May 18, 1980, and was cremated a few days later. His friends and family were devastated and confused, but his fans were riveted. The single for “Love Will Tear Us Apart” was released that June, along with a music video—the last footage of Ian alive:

When routine bites hard

And ambitions are low

And resentment rides high

But emotions won’t grow

And we’re changing our ways, taking different roads

Then love, love will tear us apart again…

This single was followed the next month by the release of Closer, which was recorded a mere two months before the singer’s death and is perhaps the most mystifying posthumous album I have ever heard. It is a suicide note set to gloomy keyboard hooks. The icy vocals describe public torture for entertainment, complete alienation, and tragic love, but most of all, Curtis’ lyrics speak of the soul-crushing guilt of a heart torn between domestic devotion and burning romance.

In truly grim fashion, Debbie had “Love Will Tear Us Apart” carved into her husband’s tombstone (which, incidentally, was stolen by some curse-thirsty jerkoff in 2008.) The grave remains a pilgrimage site for dour souls who still gather en masse on five- and ten-year deathdays.

“In a Lonely Place” was Ian Curtis’ final recording, finally released in 1981 by Joy Division’s surviving members, now known as New Order:

Warm like a dog round your feet

How I wish you were here with me now

Hang man looks round as he waits

Cord stretches tight then it breaks

Someday we will die in your dreams

How I wish we were here with you now

They might as well have slipped straight razors into the album sleeves, just in case.

© 2011 Joseph Allen

Joy Division — “Transmission”

1979