In my home state, a gigantic Confederate flag billows in the wind above Interstate 40 about halfway between Nashville and Knoxville. I have never gotten an adequate explanation as to why the controversial flag flies there or who raises it every morning—some say it is the work of Southern traditionalists, others claim it is the Ku Klux Klan—but I choose to believe that it is a tribute to the memory of Lynyrd Skynyrd’s beer-swilling singer, Ronnie Van Zant. His deathday is October 20, so without argument, today the crimson flag flies for him.

Ronnie Van Zant was born in Jacksonville, FL, where he formed a band with his fellow longhairs in high school. They eventually named their group after a crotchety gym teacher, Leonard Skinner, who had ragged them day after day about their girly locks. The coach lost a promising athlete and the world gained a Southern rock martyr. Ronnie was a born scrapper who dreamt of becoming a pro boxer like his idol, Muhammad Ali. Of course, he also harbored childhood dreams of becoming a baseball player or a stock-car racer, but like boxing, you can’t participate in those sports with princess hair. Not so for rock n’ roll. Van Zant’s fate was sealed.

Lynyrd Skynyrd did their best to distinguish themselves from the overshadowing popularity of the Allman Brothers’ brand of Southern rock. Where the Allman Brothers jammed for hours on end, Lynyrd Skynyrd composed tight, chop-heavy tracks (with the exception of “Freebird,” whose solo is long enough for you to leave the venue to buy a pint of Jack Daniels and return in time to hear the end of the song.) Still, both groups played for the War of Northern Aggression’s sore losers and their descendants, bending the black man’s Delta blues to the absolute limits of whiteness. Their redneck connection was cosmic, brother. Van Zant even dedicated “Freebird” to Duane Allman, who was shredded in a motorcycle accident in 1971.

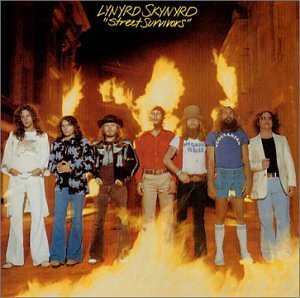

Lynyrd Skynyrd were one of the last bastions of working class White America by the ’70s. In an era of urban unrest, racially charged domestic terrorism, and the doldrums of disco, Lynyrd Skynyrd held fast the hearts of hillbillies. The rowdies were roaring for more in the autumn of 1977. Skynyrd released Street Survivors on October 17, whose album cover showed the band blazing in badass poses, about to embark on their “Tour of the Survivors.” Three days later, it all came crashing down.

The “Survivors” tour found the band traveling in a modified 1948 Convair 240 (known as the CV-300) which hobbled through the air like a drunken buzzard. On October 19 the plane—dubbed Freebird—shot an alarming stream of flames from the engine, prompting the band’s new back-up singer, Cassie Gaines, to refuse to set foot onboard again. The guys talked her out of her stubborn paranoia, however, and on October 20 she was coaxed into flying from Greenville, SC to Baton Rouge, LA. That afternoon, the rickety Convair went down in the same Mississippi swamps that spawned Robert Johnson.

According to the surviving keyboardist, Billy Powell:

Our co-pilot…had been drinking the night before and, for all I know, may still have been drunk…We hit the trees at approximately ninety miles per hour…everybody was hurled forward. That’s how Ronnie died: he was catapulted at about eighty miles per hour into a tree [and] died instantly of a massive head injury…I saw [the co-pilot] hanging from a tree, decapitated. Then I saw Cassie, who was cut from ear to ear. She bled to death right in front of me.

Paramedics arrived in time to save most of the crash victims, and to witness the nearly 3,000 bipedal vultures descend on the wreckage, stripping the site of every piece of morbid memorabilia they could sink their pink claws into. The same sort of carrion would break open Ronnie Van Zant’s Orange Park mausoleum on June 29, 2000 and lay his body on the ground. It is unclear whether they also stole the fishing pole that Van Zant was buried with, or if so, whether the grave-robbers caught any decent fish with it.

The cover image for Street Survivors was so eerily appropriate that the MCA record label pulled the album from shelves and replaced it with a less prescient cover. A few thousand copies of the original album are still in circulation among collectors. My mother has a copy hanging on her wall. It’s the sort of decoration that will keep you awake at night as the ghosts of Skynyrd stare down at you. Superstitious fans got the same screaming willies as they listened to Ronnie Van Zant sing from beyond the grave:

The cover image for Street Survivors was so eerily appropriate that the MCA record label pulled the album from shelves and replaced it with a less prescient cover. A few thousand copies of the original album are still in circulation among collectors. My mother has a copy hanging on her wall. It’s the sort of decoration that will keep you awake at night as the ghosts of Skynyrd stare down at you. Superstitious fans got the same screaming willies as they listened to Ronnie Van Zant sing from beyond the grave:

Whiskey bottles and brand new cars

Oak tree you’re in my way…

Can’t you smell that smell

The smell of death surrounds you…

On the tenth deathday of Ronnie Van Zant in 1987, the newly reformed Lynyrd Skynyrd hit the road, complete with most of the crash survivors and Ronnie’s younger brother, Johnny Van Zant, among other new additions. One by one the original members dropped off over the years, but Lynyrd Skynyrd continues to tour today as a sort of tribute band with serial rights.

Soon after 9/11, my brother and I saw Lynyrd Skynyrd: The Lynyrd Skynyrd Tribute Band play a free concert in Knoxville. The arena was full of rebel flag-bearing rednecks for whom the classic rock staple “Freebird” never gets old, and the event was sponsored by Budweiser—back when it was still an American-owned company. Between songs, Johnny Van Zant touted his jingoistic support of American troops and American military aggression as he waved an American flag above the cheering crowd.

At the peak of the show, an enormous Confederate flag backdrop came down behind the band. I remember feeling a mixture of Southern pride and shame, which generally go hand-in-hand. But no matter how out of place I felt, it was nothing compared to the one black guy whose chunky white girlfriend had popped a rebel flag hat on his head and dragged him out to the concert. It’s amazing what a man will do for love.

Perhaps Ronnie Van Zant was smiling down on us from heaven that night with an etheric Texas Hatter’s hat shading his eyes, admiring the thousands of crackers floating in his Southern rock soup. Everyone knows that ancestral spirits love being remembered. Ghosts feed on memories.

So call your local classic rock station right now and request “Freebird.” Play extended air guitar solos along with the radio. If you see a concert tonight, demand that the band play “Freebird.” Otherwise, crack open a beer, jump behind the wheel of a pick-up, and drive around drunk listening to “Freebird.” Do it for Ronnie Van Zant!

Show a cop your middle finger and yell, “Freebird!” Invade a pet store and release the parakeets and cockatiels, crying,“Freebird!” Sculpt a bird you cannot change out of titanium and smash it through a restaurant’s glass window. Then, at the top of your lungs, tell the shard-covered patrons what you just gave them.

© 2011 Joseph Allen

Lynyrd Skynyrd — “Freebird”

1977