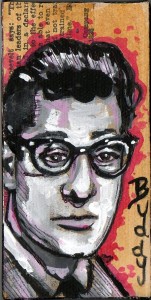

Anything cool you ever did, Buddy Holly did first. Those trend-lemming black specs? Buddy wore those when glasses were for nerds. Your hip, four-piece rock band? Buddy set that standard, son. Radical race-mixing? Buddy played with black musicians and married a Latina before such associations yielded multiculti cred—back when it got you bludgeoned by mongrels. Those teenage girls shaking hips by the jukebox? Buddy got the first slice of Miss American Pie, and by all accounts, she was home-grown cherry. And your tragic demise in the passenger seat of a hexed death-machine? Buddy beat you to it, dude. He’ll be worshipped forever, and you’ll be another statistic.

Like a sacrificial life-force, rock n’ roll was in Buddy Holly’s blood. His voice won over crowds from kindergarten on. As a teen in 1955, Buddy marveled at Elvis’ rockabilly performances, eventually opening for the King later that year. By ’56, he was recording his first singles in Nashville, which flopped. Undaunted, Buddy hooked up with recording studio manager Norman Petty, who nurtured Holly’s eclectic talents through the next hard year, and helped himself to Holly’s money when his singles finally topped the charts. Buddy’s career took off in September of 1957, only to crash in a spiraling fireball on February 3, 1959—along with stars Ritchie Valens and the Big Bopper. The Day the Music Died. That’s when record sales shot past the Sputnik.

Buddy Holly and the Crickets wrote hits about true love in an age of innocence. John Lennon was changed for life after seeing him play on TV. In fact, the Beatles’ name was inspired by the Crickets, and their first recording was reputedly a cover of “That’ll Be the Day“—whose lyrics sound like an emo suicide threat to an unrequiting lover.

Holly’s tunes echoed through subsequent careers. His chop-heavy “Not Fade Away“—a funny little ditty about male dominance, genital exposure, and an unshakable priapism—was played by the Grateful Dead a bazillion times before Jerry Garcia gave up the ghost. The list goes on and on.

A fascinating take on this all-pervasive influence comes from author Gary Patterson, of Knoxville, TN. His book, Take a Walk on the Dark Side: Rock and Roll Myths, Legends, and Curses, explores the morbid coincidences surrounding Buddy Holly’s passing. Although a few of his sources are sketchy, one gets the impression that Mr. Patterson has spent many a witching hour listening to his short-wave radio for voices of the dead—which is enough to keep me reading.

So get this: In 1957, the Big Bopper pulled a 122 hour sleepless Disc-A-Thon, after which he was carried away on a gurney. Did no one tell him that sleep deprivation can kill you? While suffering hallucinations, he claimed to have seen his own death—and apparently he enjoyed it.

On January 31 of that same year, 15 year-old Ritchie Valens missed school to attend his grandfather’s funeral. When he stepped outside, a flaming airplane fell from the sky and blew up in the distance. In a rubbernecking frenzy, his family piled into the car and followed the smoke. They arrived at Ritchie’s school, where the plane had smashed into his playground during recess. Young Valens had only just gotten over his fear of flying when he crashed two years later.

Not long before his fateful flight, both Buddy Holly and his young wife had simultaneous dreams involving plane crashes. That’s pretty weird, but here’s the real doozy, described in great detail in Dave Thompson’s Better to Burn Out: The Cult of Death in Rock n’ Roll.

In early 1958, British studio engineer Joe Meek—best known for his bizarre, yet effective recording techniques—held a Tarot session with Jimmy Miller and a mysterious Arab on a (presumably) dark and stormy night. As Meek flipped the cards, the Arab began writing automatically. The message read: “Buddy Holly Dies February 3.” Cue crackling thunder. After weeks of frantic searching, Joe Meek finally delivered the message to Holly in March, who replied with something like, “Thanks… weirdo…” and went on his way.

Scared yet?

With a pregnant wife and a flat wallet, young Buddy Holly joined the Winter Dance Party package tour in 1959. The bands traveled the frozen Midwest in a rickety bus with a broken heater, and after a wearisome performance at the Surf Ballroom in Clear Lake, Iowa, Buddy decided to fly to the next gig. Holly’s bassist, Waylon Jennings, gave his plane seat up to the sickly Big Bopper. Holly’s guitarist, Tommy Allsup, actually lost his seat to Ritchie Valens in a coin toss, inspiring Allsup to later open a bar called “The Head’s Up Saloon.” During their famous parting moment, Buddy yelled, “I hope your bus freezes over!” To which Waylon Jennings replied, “Yeah, and I hope your ol’ plane crashes!” Which, as we all know, it did.

The music didn’t just die that day—it was ground into a smoldering ball of split skulls, twisted steel, and yes, a torn scrotum. The papers related the story in grisly detail, creating the biggest, brightest, most fantastically heart-wrenching Death Icon ever—until JFK took over. AM radio stations were awash in innocent blood. Holly was 22, Valens was 17, the Bopper was 28. Dead babies, man, read ‘em and weep! Cry your fucking eyes out.

Buddy Holly’s death continued to reverberate through the music world, opening new doors and splattering them with blood. As Holly’s last release, “It Doesn’t Matter Any More,” sold by the truckload, his friend and fellow pop star, Eddie Cochran, was thrown into a full-on freak out. Eddie was supposed to be on the Winter Dance Party tour with Buddy—maybe even that doomed flight—but had skipped it to perform on The Ed Sullivan Show. Convinced that the Grim Reaper was now after him, Cochran holed up in a dark room with Holly’s records, listening to them obsessively. He even recorded a weepy tribute called “Three Stars,” but refused to release it. Instead, he gobbled tranquilizers and became a general mess.

Ronnie Smith, on the other hand, got his moment to shine when he took Buddy’s place on the Winter Dance Party. Yes, the tour carried on—less three stars, and plus one Ronnie.

David Box stepped behind those goofy specs as well, joining Buddy’s former band, the original Crickets. After their single “Peggy Sue Got Married” failed to make an impression, Box went solo and headed for Nashville with stars in his eyes.

Wayward rocker Bobby Fuller also followed in Buddy’s footsteps. Under the guidance of Holly’s former manager, the shiesty Norman Petty, Fuller broke into the charts with the fatalistic classic “I Fought the Law,” written by Crickets guitarist Sonny Curtis.

Enter the Reaper.

On April 17, 1960—as the world celebrated Jesus Christ’s victory over Death—Eddie Cochran’s car hit a light pole. He was hurled into a field along with his Gretsch guitar. The instrument was found unscratched. Eddie was smashed to hell, and died in the hospital at age 21—surrounded by the Crickets, who just happened to be in town.

On October 25, 1962, Ronnie “the Replacement” Smith was found swinging from a self-tied noose in the drug-treatment ward of a nut-house. If he couldn’t be Buddy Holly, he could at least join him.

On October 23, 1964, David Box was on a flight to Nashville to cut his next single when the little Cessna Skyhawk took a fatal nose dive. Like Buddy, he was 22.

On July 18, 1966, Bobby Fuller was found in his mother’s car near her Hollywood apartment, beaten to a bloody pulp and doused in gasoline. Coroners even found gasoline in his stomach. It could have been the LSD, it could have been the fact that Fuller was schmoozing a gangster’s special lady, or it could have been the Curse of Buddy Holly. The Law that he fought called it an accident.

On February 3, 1967, Tarot-reading doomsayer Joe Meek—who had become convinced that the late Buddy Holly was feeding him riffs from beyond the grave—blasted his landlord’s wife with a 12-gauge shotgun. He then turned the gun on himself, transforming his face into “a burnt candle,” according to one witness.

And the bad juju doesn’t stop there.

On September 7, 1978, the Who’s drummer Keith Moon was found dead in the same London apartment that “Mama” Cass Elliot had died in four years earlier. Moon had spent the previous evening at the premiere screening of the fallacious Buddy Holly Story with Paul and Linda McCartney, as well as munching one Heminevrin pill for every year of his life. September 7 happens to be Buddy Holly’s birthday.

On December 30, 1985, the Ozzy & Harriet star turned cheeseball musician, Ricky Nelson, played Buddy Holly’s “Rave On” for his final encore. He died later that night in a fiery plane crash.

Finally, on February 8, 1990, Del Shannon, a Golden Oldies favorite who spent his last days wallowing in personal sadness and antidepressants, popped a .22 caliber into his temple.* His final performance was the week before—on February 3 at Buddy Holly’s 31st Anniversary Concert and Dance,* with the Crickets as his backing band. So now do you believe in black magic?

I can already hear the smug skeptics chuckling. Circumstantial evidence, you say. Meaningless connections. Happenstance. As if your paltry intellect could grasp the lattice of coincidence underlying mundane events. You think you’re the first brainiac to cut through the mystical bullshit? Step in line, pal. Remember how Buddy Holly casually dismissed Joe Meek’s dire prophecy? Looks like he beat you to voguish skepticism, too.

© 2011 Joseph Allen

[...] [...]