Tupac Shakur was admired for being extraordinarily handsome, extraordinarily intelligent, and extraordinarily pissed off. On September 13, 1996, with five studio albums under his belt and a dozen bullets under his skin at the age of 25, ‘Pac was pronounced extraordinarily dead. Fifteen years later, his high ideals and low brow gangsta swagger continue to inspire the world’s disenchanted to raise up out of despondency—or at least, to raise up their weapons.

Tupac did time in prison before he was even born. His mother, Afeni Shakur, a radical Black Panther, was released just a month before she went into labor. She was acquitted for her alleged part in a Panther bombing conspiracy, but his grandfather (also a Black Panther) was convicted of murdering a school teacher and his stepfather spent four years on the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted List. ‘Pac came up from revolutionary fire on both the East and West Coast. It only makes sense that he would climb out by becoming an actor, a ballerino, and an aspiring rapper during his years at the Baltimore School for the Arts. After his debut with Digital Underground in 1990—who took him on as a roadie, then a dancer, then a rapper—it wasn’t long before all eyes were on him.

At different times in his life, every man shows multiple faces to the world. Browsing through the hundreds of photos taken during ‘Pac’s life, we see every possible persona: Happy Tupac, Sad Tupac, Silly Tupac, Pissed Off Tupac, Sly Tupac, Romantic Tupac, Gangsta Tupac, Guilty as Hell Tupac, Intellectual with Spectacles Tupac, Reborn in All White Tupac, Confused Tupac, Concerned Tupac, Indifferent Tupac, and of course, the Always Thoughtful Tupac.

It’s hard to say what Tupac was thinking when he fumbled and dropped his loaded pistol during a skirmish at a Marin City music festival in 1992, which allegedly went off and fatally wounded six year-old Qa’id Walker-Teal as he pedaled his bicycle down the street. Once the weight of the matter had sunk in, it was never far from his conscience. He was less apologetic about the 1993 incident in Atlanta when his driver nearly hit two off-duty police officers as they crossed the street with their wives. The cops confronted Tupac aggressively and so the rapper popped a cap in one of their asses—literally. Having spent his early years being beaten down by life’s little insults, it was a triumphant moment indeed.

Every gangsta rapper talks about “comin’ from the real” and “bein’ real.” Not content to be lumped in with the average G, Tupac left the East Coast fold and signed with the infamous Death Row Records on the West Coast, proclaiming himself to be “the realest.”

“We’re just being who we are,” he maintained. “It’s beyond good and evil. It’s Thug Life.”

Thug Life was so near to ‘Pac’s heart, he had the words tattooed on his stomach with a bullet in place of the “i.” Jon Pareles—sounding like the biggest cracker on the cheese plate—described Tupac’s position thusly in The New York Times: “In some raps, Mr. Shakur glamorized the life of the ‘player,’ a high-living, macho gangster flaunting ill-gotten gains.”

To hear Tupac tell it on his later records, you’d think he left a pile of dead gangstas in his wake that would stack to the moon. His unique style is so impassioned, so convincing, so enthralling, that it is hard to listen without feeling the youthful desire to unleash total violence on your enemies. One envisions Wrathful Tupac, Blood-soaked Tupac, Absolutely Invincible Tupac.

Despite such brash claims, Tupac’s gangsta bona fides were called into question by ostensibly “realer” detractors. Was he a true G or just a former ballerino playing out his violent fantasies in a campy performance of The Thugcracker? While in prison on sexual assault charges, Not Guilty as Hell Tupac did a bit of backpedaling, telling Vibe magazine:

“This Thug Life stuff, it was just ignorance. My intentions was always in the right place. I never killed anybody, I never raped anybody, I never committed no crimes that weren’t honorable—that weren’t to defend myself.”

The years spent as Accused Sodomite Tupac—from the date of the alleged rape in late 1993 to his release from prison on appeal two years later—were to become a dramatic turning point in the rapper’s state of mind. Tupac claimed to be the victim of an opportunistic set up by a “dumpy” groupie; his accuser claimed to be the victim of a humiliating gang rape instigated by the rapper. No one but God can judge ‘Pac at this point, but the jury found him guilty of sexual abuse.

On November 30, 1994, the day before Tupac’s sentencing for sexual assault, he walked into Quad Recording Studios in Manhattan where Biggie Smalls and Puffy Combs happened to be upstairs. Two gunmen in army fatigues drew on Tupac and his crew, demanding their jewelery. Tupac refused, so one of the men popped five bullets into him. One of the shots went straight through his nutsack. Bloody and confused, Tupac found himself upstairs with Biggie and Puffy. Tupac later claimed that the two were completely aloof toward him before the ambulance arrived, as though they were surprised that he made it upstairs. Until his death two years later, Tupac suspected that the East Coast rappers were somehow involved in the shooting.

Despite Tupac’s pitiful, bullet-riddled, wheelchair-bound presence in the courtroom the next day, the judge sentenced him to hard time in Riker’s Island Prison—where he became the first artist to have an album reach #1 while behind bars with Me Against the World. He wound up serving only nine months before his appeal, but it was long enough for the rapper to recover his potency and return to his radical roots. He immediately began recording All Eyes on Me with Death Row Records upon his release on bail.

“What I learned in jail is that I can’t change,” Tupac told a KMEL interviewer in April 1996. “I can’t live a different lifestyle—this is it…All I’m trying to do is survive and make good out of the dirty, nasty, unbelievable lifestyle that they gave me. I’m just trying to make something good out of that.”

Despite the relentless violence of tracks like “Hit ‘Em Up”—in which he promises to rain bullets on Biggie Smalls and the whole of the East Coast in a Rambo-esque tirade—Tupac would redeem himself to liberal observers by trying to help ghetto kids turn their lives around through mentoring and organized sports. As his social consciousness and dramatic delusions of grandeur gained momentum, he began to refashion himself as a militarized revolutionary icon.

“I’ll follow any great man, black or white,” he stated in his last interview. “I’m gonna study him, learn him, so he can’t be great to me no more…

“[I'll take] the discipline, the seriousness, and the bond that the Mob has, take the enthusiasm, the morals, and the principles that the Black Panthers had…take the ‘all of us as a team’ that the police have…[take the] ‘whatever we got to do to be Number 1” that the United States has…

“That’s what makes me unstoppable…

“I didn’t get that power from guns, because there’s no guns in jail, I got that power from books, and from thinking, and by strategizin’—that’s what I want little niggas to see…

“When the East Coast, and the West Coast, and the Middle Americans get together we got power…and that’s when we closer to Armageddon…

“I’m the future of Black America.”

On September 7—coincidentally, the birthday of Buddy Holly—Tupac attended a Mike Tyson boxing match at the MGM Grand in Las Vegas with Death Row founder Suge Knight. After the fight, Tupac and his entourage spotted an alleged Crip “Orlando” Anderson in the hotel’s lobby, who had supposedly robbed one of their homies at a Foot Locker some time earlier. Anderson immediately became the guest of honor at a Death Row boot party.

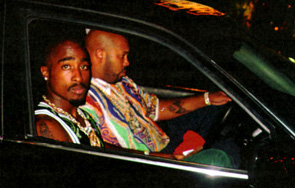

Satisfied that justice had been served, Tupac climbed into Suge’s BMW and set out for Club 662 followed by a convoy of riders. A photographer snapped the famous last photograph—Do I Know You, Muthafucka? Tupac—about twenty minutes before a white Cadillac pulled alongside the convoy and peppered Suge’s BMW with hot lead. Suge made it out with a flesh wound on his dome, but bullets slammed into Tupac’s hand, leg, and torso, shredding his right lung. After fighting for his life for six days, ‘Pac no longer had to wonder if heaven has a ghetto. His murder stirred up various accusations of police cover-ups, conspiracy theories, and false leads, yet his killers still remain at large.

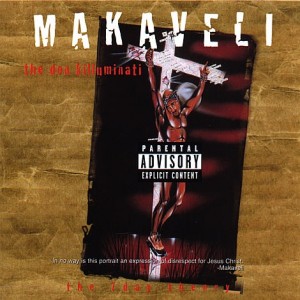

The media unleashed a sensationalist frenzy that put the national spotlight on gang violence—stoking the mythical rivalry between the East and West Coasts—and exalted a new rock star martyr to the right hand of Elvis Presley. Three weeks later, Death Row released the first of eight posthumous ‘Pac albums under the pseudonym Makaveli, entitled Don Killuminati: The Seven Day Theory. The tracks were written and recorded in three days and then mixed over the next four days. The album’s cover is perhaps the most brazen facsimile of the Christ image ever produced by pop culture, given the circumstances. Surrounded in mystique and subject to endless synchronistic interpretations, Don Killuminati sold 664,000 copies in its first week and over four million to date.

The media unleashed a sensationalist frenzy that put the national spotlight on gang violence—stoking the mythical rivalry between the East and West Coasts—and exalted a new rock star martyr to the right hand of Elvis Presley. Three weeks later, Death Row released the first of eight posthumous ‘Pac albums under the pseudonym Makaveli, entitled Don Killuminati: The Seven Day Theory. The tracks were written and recorded in three days and then mixed over the next four days. The album’s cover is perhaps the most brazen facsimile of the Christ image ever produced by pop culture, given the circumstances. Surrounded in mystique and subject to endless synchronistic interpretations, Don Killuminati sold 664,000 copies in its first week and over four million to date.

Tupac’s story continues to inspire various disillusioned and angry youths across the globe with his tragic mythos and fierce lyrical skill, which keeps him enshrined as another secular Son of the digital God. His meteoric rise and abrupt fall reveal the grinding contradictions between empathic idealism and the craven animal impulses that arise in every human heart. His own ideas on the nature of good and evil are poignant:

“I’m the religion that to me is the realest religion there is…I think that if you take one of the “O’s” out of ‘Good’ it’s ‘God,’ if you add a ‘D’ to ‘Evil’, it’s the ‘Devil’…

“The bible tells us that…because [God's chosen] suffered so much that’s what makes them special people. I got shot five times and I got crucified to the media. And I walked through with the thorns on and I had shit thrown on me…I’m not saying I’m Jesus but I’m saying we go through that type of thing everyday. We don’t part the Red Sea but we walk through the hood without getting shot. We don’t turn water to wine but we turn dope fiends and dope heads into productive citizens of society. We turn words into money. What greater gift can there be?”

It’s easy for uptight folks to write Tupac off as a failed messiah, a whining hypocrite, a narcissistic fruitcake, or a wannabe warlord, but we’ll let him have the last word on his legacy:

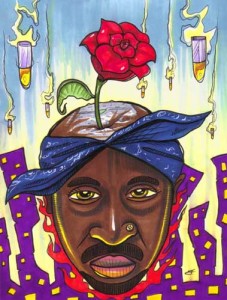

“[If] you saw a rose growing from concrete, even if it had messed up petals and it was a little to the side, you would marvel at just seeing a rose grow through concrete. So why is it that when you see some ghetto kid grow out of the dirtiest circumstance and he can talk and he can sit across the room and make you cry, make you laugh, all you can talk about is my dirty rose, my dirty stems and how I’m leaning crooked to the side—you can’t even see that I’ve come up from out of that.”

© 2011 Joseph Allen

2Pac Shakur — “Dear Mama”

1995