The Vietnam War stirred a stunning spirit of rebellion in America’s youth, and folk singer Phil Ochs was at the front of the picket line to rouse the rabble with a tune. Like Bob Dylan, Phil Ochs used his acoustic guitar to skewer the warmongering authorities and wowed the ladies with his earnest eyes. But unlike Bob Dylan, Phil Ochs did not go on to capriciously convert to a succession of Abrahamic religions, wear clownish white suits, paint his old face with girly make-up, or launch multiple comeback tours.

The Vietnam War stirred a stunning spirit of rebellion in America’s youth, and folk singer Phil Ochs was at the front of the picket line to rouse the rabble with a tune. Like Bob Dylan, Phil Ochs used his acoustic guitar to skewer the warmongering authorities and wowed the ladies with his earnest eyes. But unlike Bob Dylan, Phil Ochs did not go on to capriciously convert to a succession of Abrahamic religions, wear clownish white suits, paint his old face with girly make-up, or launch multiple comeback tours.

Unlike Dylan, Phil never achieved enough success to feel contempt for the stagehands who toil all day to erect his stage and lug his gear around. Phil never ordered his heavy-handed security guards to corral these grimy-pawed laborers into some dark corner backstage so that the legendary populist Bob Dylan wouldn’t have to make eye contact with the help… asshole.

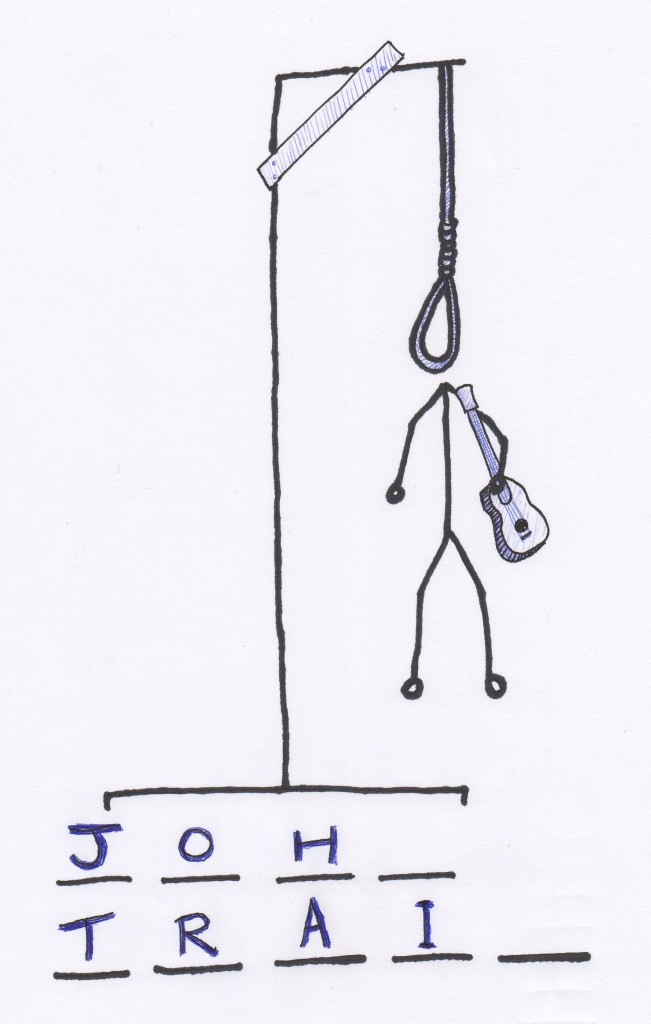

Nope, Phil Ochs was found hanging in his sister’s New York apartment on April 9, 1976 at the age of 34.

Despite the bizarre antics of the schizophrenic alter-ego which consumed him in his latter days, Phil Ochs is remembered by the radical left as a man with a message. Whether it was civil rights in Mississippi, miner strikes in Kentucky, draft-paper bonfires in Washington DC, or revolution in Cuba, Phil Ochs had something to sing about the cause. His debut album in 1964, All the News That’s Fit to Sing, earned him the title of “the singing journalist.”

While kids were getting groovy in the Age of Aquarius, their television sets were dripping with the blood of young American men and Vietnamese villagers. Kids were coming home maimed or in coffins by the tens of thousands. That’s one bad fucking trip, man.

The obvious hypocrisy of spreading democracy by way of heavy artillery became more than many could bear. American streets filled with angry youth whose radical ideas were often inspired by the revolutionary zeal that was transforming volatile nations such as Cuba or China.

What do we want?

Peace!

When do we want it?

Not next week, you asshole!

Go to any anti-war rally, and there’s Phil with his guitar. The 1965 release of I Ain’t Marchin’ Anymore solidified his identity as a voice of conscience in the folk scene. His goofy protest ditty “Draft Dodger Rag” became the feel-good hit of the Peace Movement.

The album’s title track hits a more serious note. Ochs sings from the perspective of all the young men throughout history who have marched to their deaths in war. He bore witness to the bloody Battle of New Orleans and the fratricide of the Civil War. He crawled in the trenches of Germany and heard Hiroshima’s “mushroom roar.” But Phil Ochs ain’t marching anymore, and he would appreciate it if everyone else would stop, too.

But the marching didn’t stop, and the war in Vietnam began to wear on Phil’s nerves. He threw himself into new songs. His sound began to change, utilizing more polished production techniques, and he eventually incorporated a full band. Many hardcore folk fans were furious at this new, electric Phil, but few could deny the power of his morbidly fascinated anthem, “Crucifixion.” Robert Kennedy wept when he heard Ochs perform the song on a DC train. Written as a tribute to John F. Kennedy, the lyrics could memorialize any martyr enshrined by masses:

But you know I predicted it, I knew he had to fall

How did it happen? I hope his suffering was small

Tell me every detail, for I’ve got to know it all

And do you have a picture of the pain?

[…]

So good to be alive when the eulogy is read

The climax of emotion, the worship of the dead

And the cycle of sacrifice unwinds…

Phil watched in horror as the US government went insane. The US government was also watching Phil, and the feeling was mutual. It is an established fact that the FBI and CIA were keeping tabs on troublesome youngsters clamoring for peace, and stepped in to manipulate the movement whenever possible. Some suspicious observers even accuse these powerful agencies of resorting to covert murder to stifle dissent. Poisoned tablets. Drug-induced mind control. Grassy knolls. Manchurian Candidates.

Phil’s tirades against The Man earned him a dossier in the extensive FBI files kept on dangerous “subversives” and “Communists.” After the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy in 1968, Ochs began to wonder how long it might be before “Crucifixion” was about him.

Even in the face of what he thought to be certain death, Phil refused to be quiet. In 1969 he released his last studio recording, Rehearsals for Retirement. The cover features a somber tombstone that reads:

Phil Ochs

(American)

Born: El Paso, Texas 1940

Died: Chicago, Illinois 1968

The death date is a reference to the police brutality Ochs witnessed at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago that year and the subsequent election of the ultra-conservative Richard Nixon. It must have killed his soul.

Ochs intended this last album to be Elvis Presley sings Che Guevara, but it sounds more like a jammin’ Jimmy Buffet grasping for the Revolution—and wrapping his fingers around another icy margarita instead.

Disillusioned with the radio’s refusal to play his music and America’s increasing apathy toward social idealism, Ochs set off to travel abroad in 1971. After a short spell in China, he moved on to Chile, joining folk-singer Victor Jara in support of the revolutionary Marxists that were taking hold in Latin America. Phil’s activist adventures found him running afoul of the Argentinian and Bolivian governments, from which he narrowly escaped long-term imprisonment. Shaken, he retreated back to the US before embarking to Australia, and then Africa in 1973. If there was any place for Phil to make a real difference, it had to be Africa.

One night Phil went for a walk on the beach in Tanzania. A band of thugs leapt out of the shadows and fell upon him. One held Ochs in a brutal stranglehold while the others stripped him of his possessions. His vocal chords were crushed.

Ochs refused to believe that the attack was the responsibility of savage marauders. It had to be a CIA plot. “They” had taken his voice away.

Broken and destitute, Phil returned to New York, where he flew over the cuckoo’s nest with all the grace of a crippled pigeon. The Vietnam War was finally “finished” in April of 1975. Suddenly the lifetime revolutionary was left without a purpose. Friends got worried. It wasn’t just his slurred rants about various government agencies out to get him or the countless hours spent alone in quiet misery. No, it was his insistence that he was no longer Phil Ochs that really raised eyebrows.

Phil Ochs was dead, he told people. John Train killed him. A song fragment scribbled at the time reads:

Phil Ochs checked into the Chelsea Hotel

There was blood on his clothes…

Train, Train, Train, the outlaw and his brain…

His psychotic transformation was sudden and absolute. Phil who?

John Train is a right-wing hard-ass and a whiskeybent street-brawler. John Train sings country songs and punches you in the eye. John Train don’t take no shit from nobody, especially not Bob Dylan. In one delusional tirade, a wasted John Train told his audience:

“I put out a contract on [CIA Director, William] Colby for a hundred thousand dollars. I told Colby he’s got a half year to get out or he’s dead. They can kill me but he’s dead.”

William Colby was replaced by George H. W. Bush in January of 1976, and a few months later, John Train slipped a rope around Phil Ochs’ neck and strung him up in his sister’s apartment. It would be fifteen years before the next major war. When the bombs began falling on Baghdad in 1991, Phil Ochs’ passionate voice of protest was absent—but then, so was everyone else’s.

© 2011 Joseph Allen

Phil Ochs — “I Ain’t Marching Anymore”

c. 1966