[Update: Seth Putnam died on June 11, 2011, supposedly of a heart attack at the age of 43. We wish him luck on the other side.]

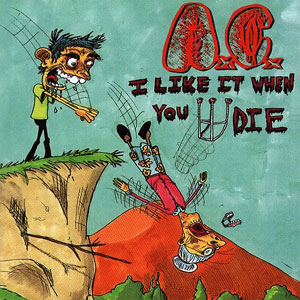

Rock n’ roll history is the story of offensive dildo-greasers getting attention for their affronts to common decency, and Seth Putnam deserves an extended footnote. Only four years after Eazy E was struck down by a horrible disease, Putnam had to go and write a silly song about it. But then, Anal Cunt’s creator and vocalist was never known for his sensitivity. His 1997 album I Like It When You Die is a series of minute-long insults set to ear-shredding grindcore.

Rock n’ roll history is the story of offensive dildo-greasers getting attention for their affronts to common decency, and Seth Putnam deserves an extended footnote. Only four years after Eazy E was struck down by a horrible disease, Putnam had to go and write a silly song about it. But then, Anal Cunt’s creator and vocalist was never known for his sensitivity. His 1997 album I Like It When You Die is a series of minute-long insults set to ear-shredding grindcore.

Like my buddy Jimmy Pop, Seth Putnam can make you feel like a real dumbshit by simply telling you what you are doing with a derisive, spirit-crushing tone in his voice. Of the fifty-two tracks on Anal Cunt’s album, songs like “You Keep a Diary,” “You’re Gay,” “You Look Adopted,” “You Have Goals,” ”You Live in a Houseboat,” and the cult classic, “You’re in a Coma” are all about how you suck.

On “You’re in a Coma,” Putnam sings:

You’re a fucking vegetable, we tried to pull the plug

But you still wouldn’t die, you’re a dumb stupid fag

You shit in a bag, you piss in a tube

You can’t walk, you can’t move

You’re in a coma

I tried to give you a hotfoot, but you didn’t notice

You’re gay and you’re in a coma

You’re a fruit and a vegetable

By eerie coincidence, Putnam suffered a brain-damaging drug overdose seven years later, which left him in a coma for some time. Half-paralyzed and shaking, he returned to the stage in a walker and performed sitting down. When asked about being in a coma, Putnam said: “Being in coma was just as fuckin’ stupid as I wrote it was.”

What a dick, right? So why are you laughing?

What a dick, right? So why are you laughing?

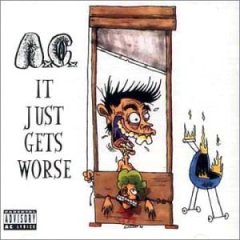

But I digress. Seth Putnam also composed a song about two notable rock star martyrs for his 1999 album, It Just Get’s Worse.

“Eazy E Got AIDS from Freddie Mercury” describes a possible romantic relationship between the tragic stars:

You went to dinner, Freddie wore a leash

You ate fried chicken, Freddie ate quiche

Many observers have noted how offensive it is to presume that a Zoroastrian would prefer to eat quiche, and I have to agree, that’s just ignorant. Furthermore, the track-list for It Just Gets Worse also includes such hackle-raising ditties as:

-

“I Became A Counselor So I Could

Tell Rape Victims They Asked For It” -

“I Sent Concentration Camp Footage To

America’s Funniest Home Videos” -

“Rancid Sucks (And The Clash Sucked Too)”

-

“You Rollerblading Faggot”

-

“I Lit Your Baby On Fire”

-

“Sweatshops Are Cool”

-

“Women: Nature’s Punching Bag”

-

“I Snuck A Retard Into A Sperm Bank”

-

“Your Kid Committed Suicide Because You Suck”

(originally entitled “Connor Clapton Committed Suicide Because His Father Sucks”) -

“Hitler Was A Sensitive Man”

-

“I Gave NAMBLA Pictures Of Your Kid”

-

“The Only Reason Men Talk To You Is Because

They Want To Get Laid, You Stupid Fucking Cunts” -

“Dead Beat Dads Are Cool”

-

“I’m Really Excited About The Upcoming

David Buskin Concert” -

“You’re Pregnant, So I Kicked You In The Stomach”

-

“I Sold Your Dog To A Chinese Restaurant”

-

“I Got An Office Job For The Sole Purpose Of

Sexually Harassing Women”

Seth Putnam (age 42) released Anal Cunt’s eighth studio album, Fuckin’ A, earlier this year. As you might expect, everyone hated it. A few very insensitive individuals went so far as to say that the riffs are “gay” and the lyrics are “retarded.”

Anal Cunt — “Eazy E Got AIDS From Freddy Mercury”

1999