Protected: “Dead” on His Last Album Cover

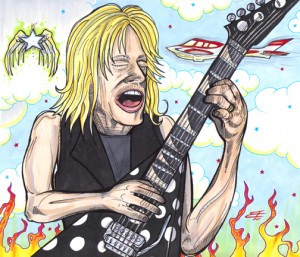

Randy Rhoads and that

Damned Beechcraft

It is questionable whether humans were ever meant to fly. The instinctive, white-knuckle terror which grips the average person at great heights is proof to many that we should just stay on the ground. Desperate prayers are uttered, pills are swallowed, lifetimes reconsidered, armrests torn from their hinges. Then the gears ease down for a smooth landing, and the Universe becomes a safe place once again—for now, anyway. While it is arguable that the laws of physics would not allow us to become airborne if we were not intended to be, gravity and high velocity are unforgiving judges of performance. Just one false move, and you’re an Icarus-splat on the dirt.

Randy Rhoads was acutely conscious of that fact, and terrified of flying. So it is curious that he came to be in the passenger seat of a Beechcraft light airplane on March 19, 1982, with the pilot executing daredevil dive-bombs over Ozzy Osbourne’s tour bus.

Ozzy had recognized Rhoads’ genius upon hearing the first note of his two-minute audition in 1980. The “Prince of Darkness” immediately invited Rhoads to record on Blizzard of Ozz. Over the course of two years, the young guitarist would ride a rising tide of permed headbangers to become a heavy metal legend. Besides his mastery of blistering metal riffs, Rhoads was also a proficient classical player, as evidenced by his elaborate solos. In fact, he remained an eager student to the end, scheduling lessons with various classical instructors on each stop of the Diary of a Madman Tour—down to his last gig in Knoxville, TN.

The band stopped for tour bus repairs on their way to Orlando, FL. As it happened, the depot was next to a small airstrip, and the wily tour bus driver knew how to get a plane off the ground (though his license had been revoked.) As the rest of the band slept on the bus, three thrill-seekers gaffled a Beechcraft Bonanza for a quick joyride: 25 year-old Randy Rhoads; the band’s hairdresser and costume designer, Rachael Youngblood; and the bus driver, Andrew Aycock, who snorted a sackful of magic pilot dust before jumping into the cockpit.

It isn’t hard to imagine what Aycock was thinking as he buzzed the tour bus like he was the rock n’ roll Red Baron. Aycock’s ex-wife, whom he’d fought with all the way from Tennessee, was down there. One can assume that the moniker “Gaycock” had been dropped on him at least once, now that she was free of his surname. Perhaps he just wanted to impress his former soulmate—or else put the fear of God into her. One way or the other, it’s clear that Aycock got cocky and his gak-fueled lunacy got the best of him.

But what were his passengers doing? Had they known they were in for a wild ride? Was Randy trying to overcome his flight phobia? Was he laughing at the gods? Screaming for his life? We will never know. On the third or fourth pass, the Beechcraft’s wing clipped the tour bus, tearing off its roof. The plane spun out, lobbed off the top of a pine tree, and smashed into a nearby mansion, exploding on impact. Everyone on board was incinerated.

Ozzy was overcome with grief for his close friend. “He was a saint,” the singer said of Rhoads, “He was an angel, and too good for this world. His death is always on my mind.” Although Randy Rhoads is pretty much unknown outside of heavy metal circles, his California gravesite still attracts scattered throngs of shredder devotees on his deathday.

The Mr. Crowley EP quickly became the best-selling picture disc of all-time, but sadly, Osbourne’s subsequent albums would never have the same bite after Rhoads’ passing. The band’s mullets would never be so skillfully feathered after the loss of Rachael Youngblood, either. That Ozzy did not follow them to the grave directly is a striking testament to his pact with the dark gods of this world. He later joked: “Had I been awake, I’d have been on that plane—probably sitting on the fucking wing.”

It seems that a rock star’s natural impulse is to defy gravity. High on drugs, high-dollar whores, high society, traveling at high altitudes—it all just comes with the territory. Rigorous tour schedules and stunning wads of pocket money put successful musicians on the next flight to somewhere, day after day. It’s no wonder that some crash to the ground—particularly those flying in light private planes.

The Beechcraft was the martyr-making death machine in early rock n’ roll history. Its first victims were claimed on February 3, 1959—the Day the Music Died. Buddy Holly, Richie Valens, and J.P. “Big Bopper” Richardson boarded a 1947 Beechcraft Bonanza—the first in the Bonanza series—departing Clear Lake, IA. Taking off in the fog and snow, their plane barely made it five miles before disappearing from radar. Of course, all three artists reappeared at the top of the pop charts.

On July 31, 1964, “Gentleman” Jim Reeves hit a thunderstorm ten miles out of Nashville, TN and crashed his Beechcraft 35-B33 Debonair into the woods—just a year and a half after Pasty Cline had come to a similar end. In fact, Jim Reeves had taken pilot lessons from the same instructor as Patsy’s manager, Randy Hughes, who flew the plane she died in. Predictably, Reeve’s country ballad “I Love You Because” became the best-selling single of 1964 after his death.

On December 10, 1967—three days after recording the aqueous tune “Sitting on the Dock of the Bay”—Otis Redding was plunged into the freezing waters of Lake Monoma outside of Madison, WI. His death machine was a twin-engine Beechcraft H18, which made it less than four miles from the runway before spinning out of control. All but one of the passengers either drowned or succumbed to hypothermia. Redding’s memorial drew 4,500 people, and his posthumously released R&B record sold 4 million copies.

Jim Croce, whose rock hit “Bad, Bad Leroy Brown” was the baddest tune in the whole damn town, had recently lost his luggage on a major air-carrier. Sick of the hassles, he hired his own Beechcraft E18S to fly him and his band out from Natchitoches, Louisiana on September 20, 1973. They may have over-packed a bit, because the pilot failed to gain sufficient altitude while taking off. The plane clipped some trees at the end of the runway and smashed into the ground. Released after his death, “I’ll Have to Say I Love You in a Song” seems strangely poignant in light of the accident.

The Beechcraft’s ferocious appetite eventually subsided after Randy Rhoads died in 1982, giving way to a variety of other star-hungry vehicles. In 1985, teen idol Ricky Nelson’s DC-3 went down in a ball of flame. In 1990, Stevie Ray Vaughn’s helicopter crashed into a ski slope. In 1997, John Denver crashed his Rutan Long-EZ into the Monterey Bay. And in 2001, up-and-coming star Aaliyah was killed when her coked-up pilot couldn’t get the overloaded Cessna 402-B to the end of the runway before crashing.

Statistically, flying is supposedly sixty times safer than traveling in an automobile—except for rock stars. You’d have to be suicidal to cut a hit record—or, err, upload a widely pirated MP3 album—and then step on board a small plane. Sure, you might take heart knowing that aircraft fatalities have fallen steadily in developed countries since the early 1970s. It may relieve some anxiety to hear that 2010 was the third year in the last four in which there were no U.S. airline fatalities. For nearly ten years now, no major star has died in an air crash. It is possible that as aviation safety technologies continually advance—and rock stars avoid ultralight planes—the Gods of Death have become more merciful. You’d better hope so, Mr. Superstar. Otherwise, the Ancient Ones are getting plenty thirsty for the next martyr’s blood.

© 2011 Joseph Allen

“Mr. Crowley” — 1980