If you didn’t know that today is the 15th deathday of Bradley Nowell, don’t feel bad. Millions of kids bought up Sublime’s 1996 self-titled album—released two months after the singer overdosed on you-know-what in a San Francisco hotel room—but most didn’t know he had died. Nowell is what you might call a late-start martyr, illuminating an otherwise seedy state of affairs with his posthumous halo.

What kind of asshole pawns his band’s equipment right before a gig, casually shits his pants on clonidine patches, and kills himself one week after his wedding and two months before his album goes platinum? A junky, that’s who.

That’s not to say that Brad wasn’t loved. His many friends, his wife, his one year-old son, and his loyal dalmatian absolutely adored him. He was the sort of shirtless surfer boy that has you laughing beer out your nostrils as he recounts the time you accidentally stuck your finger on his dirty needle while fishing for change under the couch cushion. It shouldn’t be funny, but it’s all in the delivery. Charismatic drug-addicts are a lot like cult leaders, lawyers, and cynical writers—totally lovable despite being self-centered pricks.

Bradley Nowell embraced elitist heroin chic like a hipster’s skinny jeans cling to his sweaty butt crack. All the dead rock stars were doing it, and Brad wasn’t about to be left out. Janis Joplin and Sid Vicious were immortalized with a spike to the vein like a nail in the palm. Just like GG Allin, Kurt Cobain, and Shannon Hoon in the early 90s, Bradley Nowell’s body was found stabbed full of more holes than a desperate fat girl who wields a pocket-knife on herself so the entire football team can get it on with her simultaneously. It was an attention thing.

Funny thing is, the wider world never cared about Nowell’s personal struggles until the year after his death. Before that he was just an evening’s worth of good vibe guitar licks bouncing around the Long Beach party scene.

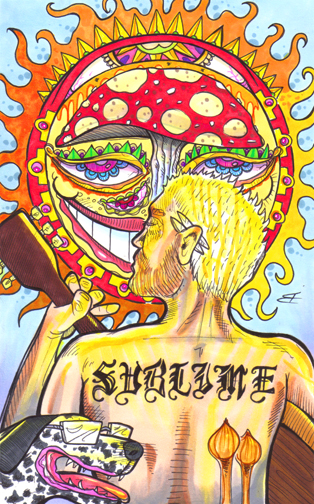

Sublime sold more than 60,000 copies of their 1992 debut 40 oz. to Freedom out of the trunk of a car. They recorded their second album, Robbin’ the Hood, in an obscure Long Beach crackhouse. It was only after a local radio station repeatedly played their peppy single “Date Rape” in 1995—which playfully describes the karmic odyssey of a horny scumbag who goes from picking up victims at the bar to getting forcibly fucked behind bars—that Sublime was given their shot at the national spotlight.

Brad had to do a long stint in rehab to finish off his self-titled mainstream masterpiece, Sublime. The album is a brilliant mix of punk, folk, and reggae—polkeggae, if you will. He kept it together just long enough. Two days after his Vegas wedding, Nowell was back on the road and back on the smack, and within five days he was flat on his back and zipped in a sack. With one hot shot he traded his long dreamt-of success, his fatherhood, and God knows how many surfside barbecues for six feet of dirt and a bucketful of worms. Is there such a thing as buyer’s remorse in the afterlife?

To commemorate Nowell’s passing, my girlfriend and I spent last night listening to his last album under a sweet cloud of schmoke-well. As with “Date Rape”, the most popular tracks on Sublime obscure Nowell’s twisted subject matter with catchy, upbeat tunes. When I was a teenager, Sublime was just the stony soundtrack to my two joints in the morning and two joints at night, not a nightmarish voyage into the heart of darkness. My, how perception changes with age.

We tapped our feet to “Wrong Way” and sang along to the story of some pervo protagonist driving off with a fourteen year-old prostitute who was broken in by her father and seven brothers, only to have this crafty Lolita steal his car as the cops drag him away. “Santeria” is another love song about reclaiming a street-stepping sweetheart by blowing her new boyfriend’s head off and slapping the shit out of her in full on caveman style. Great mood music for a romantic evening.

“April 29, 1992 (Miami)” is a relaxing romp through the Rodney King riots—a cracker loot anthem about snatching up consumer goods and burning down Babylon for fun. At one point Nowell becomes indignant that certain demographics are overlooked in the chaos:

They said it was for the black man

They said it was for the Mexican

And not for the white man

But Nowell finds that some pastimes transcend race:

It’s about coming up

And staying on top

And screamin’ “187 on a muthafuckin’ cop!”

By the end of the song, my girlfriend and I were ready to take to the streets with Molotov cocktails, but were too blitzed to be bothered. Besides, we had a riddle to unravel.

Sublime’s biggest feel good hit is undoubtedly “What I Got”. On the surface, the tune is as blissfully optimistic as any fortune cookie prediction. But the wise Chinese buffet-goer knows that you have to decode the otherwise vacuous message by adding “in bed” to the end, as in:

“You find beauty in ordinary things, do not lose this ability in bed.”

“Humor usually works at the moment of awkwardness in bed.”

“It takes more than good memory to have good memories in bed.”

“Ideas are like children; there are none so wonderful as your own in bed.”

Through a similar cryptographic analysis, we were able to decipher the true meaning of “What I Got” by reading between the lines:

Early in the morning, risin’ to the street

where there’s heroin

Light me up that cigarette and I strap shoes on my feet

to find heroin

Got to find a reason, a reason things went wrong

heroin?

Got to find a reason why my money’s all gone

because heroin

I got a dalmatian, I can still get high

on heroin

I can play the guit-tar like a motherfuckin’ riot!

which sounds like a drowsy musician struggling to play his instrument while on heroin

Life is too short, so love the one you got

like you would heroin

‘Cause you might get run over or you might get shot

up with too much heroin

[…]

I don’t cry when my dog runs away

because heroin is more important

I don’t get angry at the bills I have to pay

I pay my dealer instead

I don’t get angry when my Mom smokes pot

because nobody likes a hypocrite on heroin

Hits the bottle and goes right to the rock

Fuckin’, fightin’, it’s all the same

when you’re on heroin

Livin’ with Louie dog’s the only way to stay sane

other than heroin

Let the lovin’, let the lovin’ come back to me

or maybe just give me more heroin

Lovin’ is what I got

that, and a spoonful of heroin

I said remember that…

If only anti-drug campaigners had a sliver of the talent Bradley Nowell possessed, there might be no more drug users inspired to write music as powerful as Sublime made. I often wonder if the drugs open artists up to their fantastic potential—as Nowell believed heroin did for him—or if the music in their souls is simply strong enough to pour out despite the dope.

Did Bradley Nowell shake off his mortal shitbag for sake of a stupid smack habit, or did he ride the Tao into the jagged rocks of Destiny? Perhaps the answer is somewhere in between, as ambiguous as a Yin-Yang decal on a freshly waxed surfboard.

The ancient Tao Te Ching say: “True words are not beautiful. Beautiful words are not true (in bed).”

© 2011 Joseph Allen

Sublime — “Badfish”

1992