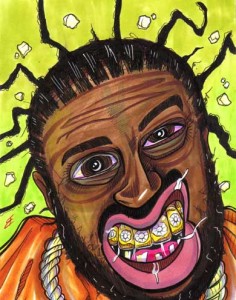

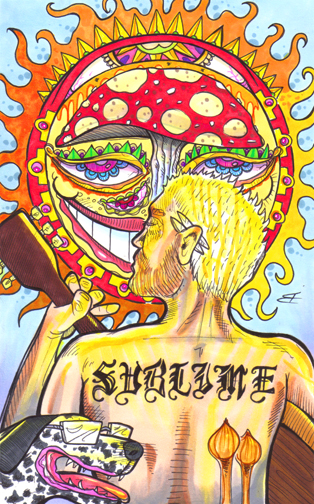

Ol’ Dirty Bastard’s slurring, incoherent “singin’ rappin’” rhymes hit the mic so hard, you have to wipe oozing spittle off your face after listening to his deranged tracks. He spoke the tough truth from the mean streets, delving into the dark crevices of ghetto crackhouses and bitch’s booties, coming out the other side covered in doodoo brown and flashing a steel grille grin all the while. Some believe that the big “G” Government took notice and were highly pissed about it.

Raised in the housing projects of Brooklyn, ODB broke out with the “world domination” scheme masterminded by his cousins, RZA and GZA, whose hip hop exploits are succinctly described by Dirty’s biographer, Jaime Lowe:

“The foundation of Wu-Tang is in its lore, its urban mythology, its appropriation of kung fu, chess, Buddhism, Islam, bible studies, cartoons, comics, Staten Island; anything they came across was woven into an intricate web of culture and identification and a constructed community that bordered on cult. They made themselves a world when the projects didn’t provide. And they sold that world to this other world (a primarily suburban one) in rhymes”

During the 1998 Grammy Awards, Ol’ Dirty Bastard stepped all over singer/songwriter Shawn Colvin’s shining moment when he stormed the stage to declare the Wu Tang Clan’s noble purpose to the world:

“I don’t know how ya’ll see it, but when it comes to the children, Wu-Tang is for the children. We teach the children.”

The day before, MTV broke the news that Ol’ Dirty Bastard had witnessed a gruesome car wreck in New York and immediately rallied his homies to lift a vehicle off of four year-old Maati Lavell, whom he reportedly visited in the hospital during her recovery. Perhaps he imparted the same sort of Nation of Islam-inspired fatherly advice that he gave during his relatively lucid if typically rambling “barefoot in Brooklyn” interview:

“’The black man is God’…This is for the children…To all my little bastards out there, my bad bastards, keep being bad, just make sure you get a good education in school. You ain’t gotta tell yo’ teacher off, tell yo’ teacher off with education…Bomb his ass! Know’m'sayin’? White devil muthafuckas…Yo, but um, no, when I say white devil, I’m just sayin’ that, you know, you got some good devils, you got some bad devils, just like you got some good black men, you got some bad devil black men, know’m'sayin’, ’cause those black man is God, we know that, the white man come from the black man, so, that’s what created the devil, so we know that—Yo, where Panther wit that get high?…”

Aside from the millions of youngsters who bought Wu-Tang’s albums, Ol’ Dirty sired thirteen seeds of his own, whom he introduced to the world during an MTV News segment in which they rode in a limousine with their mother and father to collect food stamps. Typical white devil middle-class Americans might think the rapper was an enigma for taking government assistance after receiving a $40,000 advance from his record company, but Dirty’s reasoning seems obvious enough:

“Why wouldn’t you want to get free money?!”

Considering the amount of dough he would drop on defense attorneys over the next few years—including OJ Simpson first lawyer, Robert Shapiro—it’s clear that ODB needed all the cash he could get.

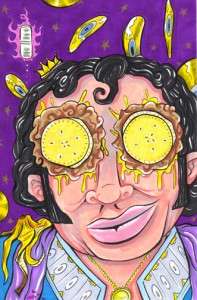

Wu-Tang Forever was released in 1997 and sold over 600,000 copies on its first day and over 4 million by year’s end. The Ol’ Dirty Bastard had already seen his 1995 solo album Return to the 36 Chambers: The Dirty Version earn a Gold certification, and with the release of Wu-Tang Forever he was flush with money and “lookin’ for new girls to put babies in.” He took on the moniker “Big Baby Jesus” and launched a new line of clothing. He bought a new grille with gleaming fangs. He also incinerated hard cocaine like he had to burn the evidence.

Given his outspoken suspicion of “the Government,” I imagine that more than one hub got sucked down in one lung-full for fear that the shadowy agents peering back through his cracked motel blinds would soon kick down the door. ODB’s views on the Government went well beyond the persecution of drug users, though, as he explained to TRL viewers across the world in 1998:

“Everybody’s scared of the Government, know’m'sayin’, because they killed Tupac, and they killed Biggie Smalls. I don’t care what y’all say, that’s my seein’…”

The crowd laughed, but Jesus wasn’t joking. Carson Daily must have known that the veil had been torn. A ghetto star had just stated on national television that the Government assassinated two high profile hip hop stars, presumably to keep them from uniting black people against the system. Could there be a more sure-fire way to join them? But Big Baby Jesus (aka Osirus [sic], aka Dirt McGirt) was unafraid. He had provided a safe place for these martyr’s souls to occupy, as he explained to a Swedish interviewer during Wu-Tang’s world tour:

“Notorious ain’t dead, Tupac ain’t dead, they exist within me…they came to me and said, ‘Dirty, Dirty, wake up, wake up, yo man.’ I said, ‘Well come on in!’

“So they not dead. They live in me now, you know, they right here…that’s why they call me Osirus…’cause I went to the next dimension…you see, I already mastered the human lessons…I had to go to the other dimension where it’s all thought, you know, we call it the Land of Nobody…Tupac is right here, and Biggie Smalls right here, they just on my shoulders, you know, you just gotta see ‘em…”

Is that why the authorities were constantly harassing ODB to the end of his days? Perhaps the Government was trying to capture and silence the incorporeal hip hop entities that It had endeavored so stringently to snuff out. Why don’t other people see it? I mean, just think about it, man. Connect the dots. Open your eyes. Read between the lines. See through the smokescreen. Freak the fuck out.

ODB had only been in trouble here and there before the release of his solo album: petty convictions for assault and failure to pay child support. Then suddenly, after his rise to stardom in 1997, the criminal charges were relentless: attempted assault against his wife, shoplifting sneakers, two counts of criminal threatening, shooting at police officers, driving without a license, possession of a bulletproof vest as a felon, possession of marijuana, and the coup de grâce in 1999, possession of twenty vials of crack cocaine. It’s pretty clear that shadowy forces were out to destroy him.

Apparently the Government did not control every government institution, as some of the charges were dropped. But ODB’s conviction for crack in 2000 got him sentenced to six months in rehab. Ol’ Dirty Bastard was never one to be confined, though, and four months into his (mind control?) treatment he jumped the fence. One month later, the police were called when an unruly crowd gathered at a McDonald’s in Philadelphia. Officers found Dirty signing autographs in the parking lot. He was extradited to New York and sentenced to four years in Clinton Correctional Facility—the same maximum security prison that Tupac served time in.

Prison is no fun for anyone—except for agoraphobic sadists and man-loving masochists, of course—but the experience completely destroyed the Ol’ Dirty Bastard. His leg was broken in an attack by inmates (or was it the guards?) Some say his jaw and nose were broken as well. An interviewer for Blender magazine found Dirty tense and understandably paranoid behind bars, unsure where the next assault might come from. New York’s Daily News reported that ODB was diagnosed as schizophrenic at the Manhattan Psychiatric Center before being locked up, so the cold concrete and leering faces must have been a terrifying realization of his darkest delusions. Add to that the unquenchable libido of a man reputed to wrap gauze around the friction burns on his dick before donning a condom, and it is easy to see how incarceration would break Dirty’s mind and spirit.

“You know, I don’t know whether Ol’ Dirty Bastard is even here any more,” ODB told Blender before returning to his cell. “I think he’s gone.”

Dirty was finally released in 2003, but friends and family say that he was never the same after that. During his first show at the Knitting Factory in Manhattan he froze up completely, staring at the pale-face hipsters in the audience with tears streaming down his cheeks. Subsequent shows were not much better. Offstage he was quieter, subdued, detached. He was prescribed antipsychotic medication which causes all of the body’s fat cells to swell, blowing the rapper up like he’d been tapped with an air pump, face, fists, and all, and after laying awake for three years in prison, it seemed that all he wanted to do was sleep. Of course, none of that stopped ODB from chasing the ladies.

“Every day, like probably three times a day, I jerked my dick off so much that the prisoners was actually sayin’ ‘Yo, Dirty, chill the fuck out!’, know’m'sayin’, because I couldn’t help it—every bitch I saw on TV, her ass looked as funny to me…I’m into all asshole. I like it ’cause it’s tinier than the pussyhole, you know, it’s so tiny it’s like tiny as a clitoris, so when I…get the feeling of licking a York Peppermint Patty, it’s a sensation…”

One gets the feeling that Dirty’s public claim that he “got burnt two times by gonorrhea” is a bit of an understatement.

Despite his continual mental breakdown, the future held at least some promise for the star. Dirty began working on new recordings for Roc-A-Fella Records, was offered half a million up front, and even moved out of his mother’s apartment into his own place. But neither his recording obligations nor policing by his manager and parole officer could deafen Dirty’s ears to the siren song of shiny pearls bubbling in a Cho’ Boy-stuffed glass rose tube. The Government was coming for him anyway, so why should it matter? He explained his dilemma during a promotional documentary recorded before his death, with his hooded eyes moving independently of one another:

“Of course, the Government has it out for me, because…see I’m a man-made product…You made me! Yundastand wha’m'sayin’?…You got your government here [makes sweeping gesture to the perceptible cosmos], it’s a world of one thing and I happen to be another thing that’s governed, too. And I guess now it’s my time…

“It’s time to move on. It’s time for Ol’ Dirty Bastard to not exist no more. It’s time for a new Ol’ Dirty Bastard, you know, a baby Ol’ Dirty Bastard…and that’s just how it is. The Government is out to assassinate me and get it over with.”

On November 13, 2004, nine days before his parole would have ended and two days before his 36th birthday, Dirty spent the afternoon smoking crack and eating opiates. He wound up at the RZA’s recording studio, 36 Records in Manhattan, where he collapsed in the lounge. EMS workers arrived within half an hour, but Dirty was pronounced dead at the scene. The Government had finally gotten to him.

Some critical observers deride the ODB as a cynical one-man minstrel show who intentionally played up to the white man’s warped prejudices toward blacks—a callous, slovenly rake who went out of his way to become the cartoonish embodiment of every demeaning racial slur. But I don’t see a fundamental difference between ODB and any other celebrity whose excess and self-destruction become fodder for public amusement.

Others applaud him for his sincerity, and for rubbing the legacy of slavery and subsequent racial oppression in the face of indifferent whites. Rather than regard him as a trainwreck of poor decision-making, they see a tragic victim of the system—the Government.

Steve Huey states in his allmusic.com biography: “The saddest part of his story is that, in the end, the only person he truly harmed was himself.”

So ODB’s story would have been less sad if he’d taken a few dozen others down with him? If you say so, Steve.

I would think the saddest part of the story involves the people that Dirty left behind. Over three thousand people gathered at the Christian Cultural Center in Brooklyn to pay their respects to the Ol’ Dirty Bastard (aka “Rusty Jones” to his devastated mother, aka “Daddy” to his thirteen kids, aka “Brother” to his friends.) Millions more remember him fondly as an artistic pioneer—the rapper whose style had no father, and yet he became the father of Crack Rap. As RZA put it, “His growl, his voice, and his delivery was one of the most unorthodox voices in hip-hop.”

Personally, I am inclined toward Dirty’s philosophical view of himself, which can be read as a sort of self-absorbed self-elegy, well-suited for a rock star martyr:

“Ol’ Dirty Bastard was something that was created from God…God created Ol’ Dirty Bastard: his walk, his talk, his movement, his step, his feet, his everything…his smell, his breath of life, his heartbeat…God did it. Know’m'sayin’?”

© 2011 Joseph Allen

Ol’ Dirty Bastard — “Shimmy Shimmy Ya”

1995