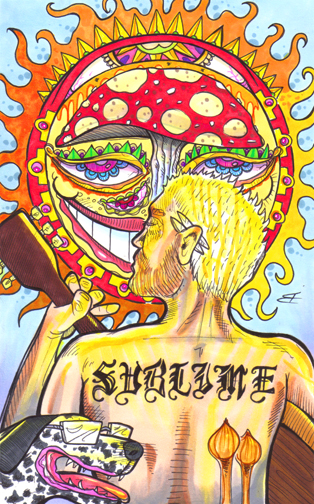

Every rock fan abandons sanity to star-worship at some point, but Deadheads took rock n’ roll deification to unprecedented levels. Following their favorite band became a spiritual vocation. Jesus had his multitudes, Marx had his Maoists, and Jerry Garcia had his Deadheads. Through the magic of vicarious identification, the icon and his devotees become One.

According to Jerry’s followers, The Grateful Dead created more than endless, noodling tunes for acid-drenched white kids to spin around in circles to. For diehard ‘heads, Dead shows were a nomadic religious rite. The Dead’s ethos and aesthetic provided a cultural raft upon which the communal idealism of the 60s could keep on floating through the money-grubbing 80s, with Jerry Garcia—aka “Captain Trips”—at the helm.

The spiritual significance of The Grateful Dead’s improvisational live performances still reverberates through the hippysphere. Most of the Dead’s 2,314 shows were captured for posterity on coveted bootleg recordings which continue to stir whirlwinds of reefer smoke, acid dreams, and flailing dreadlocks from San Francisco to Jerusalem. Jerry Garcia saw himself as a free-styling musician with a powerful imagination and even more powerful appetite, but the caravans of societal dropouts who followed him back and forth across America regard him as a psychedelic shaman pouring forth an endless fount of positive vibes.

God only knows what sort of bizarre visions swirled in Jerry Garcia’s shaggy dome. He dropped LSD for the first time in his early twenties and never looked back from the bandwagon’s driver seat. Captain Trips ate enough acid to make playing a three hour bluegrass song seem like a pleasurable diversion. Everyone agrees that without the psychedelic revolution, The Grateful Dead would have never become world famous—as in the old joke:

—What did the Deadhead say to his buddy when the drugs wore off?

—Man, this music sucks!

How appropriate that Garcia came into the “love generation” limelight at Ken Kesey’s mind-twisting Acid Tests during the mid-60s. His band’s trippy take on popular R&B songs set the ambiance as soul-searching seekers had their psyches ping pong paddled by The Merry Pranksters’ clever skits, groovy visuals, and gallons of electric Kool-Aid. It was in this brain-mush stew that Garcia started cooking his one true love—the legendary Mountain Girl, with whom he would have his second daughter. The revelry must have been a welcome relief after his tough upbringing.

Jerry Garcia grew up in hardscrabble neighborhoods in San Francisco. A dark star presided over his youth. His father was swept to his death by rapids during a fishing trip, which Garcia claimed to have witnessed despite others’ insistence that he was not present. Jerry’s older brother accidentally chopped the boy’s finger off with an axe as he held a piece of wood, yet Garcia showed promise as a musician despite the injury—although any shot he may have had as a shadow puppeteer was surely ruined. At the age of sixteen he was thrown out of a windshield in a car accident which killed his friend. That was the pivotal moment, Garcia said later, which convinced him to stop lollygagging and dedicate himself to music.

The 60s were a time to share and share alike—particularly one’s drugs—so it is fitting that The Grateful Dead started out by living communally at 710 Ashbury under the guidance of Owsly Stanley, the LSD-brewing mad scientist whose innovations in live sound revolutionized the art of large-scale concerts. This interplay of individual genius and egalitarian idealism would characterize the Dead’s career for the next three decades. The band produced a fractal array of complex musical improvisations for the homogeneous horde, becoming fantastically wealthy as their perpetually migrating fans struggled to peddle grass and grilled cheese sandwiches. Throughout the 60s the Dead enjoyed only modest success with a dedicated cult following (their brief Woodstock performance didn’t even make it into the film,) but they would go on to become the embodiment of all that is hippy after the 70s boogied most of their peers into dancefloor sludge.

It was during that era of disco fever that Jerry discovered the vitalizing wonders of cocaine, trading mind-expanding trips for tongue-wagging insomnia. By the mid-70s the band’s following had swollen to include a new generation of nomadic dust bunnies dedicated to attend every last show—no matter how far the drive—and the starry-eyed “custies” to whom they plied their wares.

Shakedown Street was a spontaneous, if self-regulating open air market which sprang up in the parking lots outside of every Dead show. This lot scene was a sub-economy for otherwise jobless drifters. There were tie-dyes and teddy bears, skeleton posters and skull t-shirts, burritos and lightning bolts, magic crystals and hemp jewelry, and of course, more neuron-jiggling drugs than you could shake a didgeridoo at.

Despite being a commercial hub of intoxicants and scalped tickets, the lot scene offered the allure of communalism and togetherness, where the haves could bestow kindness and the have-nots could have fun, where an otherwise lonesome misfit could be with ten thousand of his closest friends. Dead shows were a universe unto themselves, a place apart from the soulless, confining, stingy mores of middle class life. The possibility of spiritual transcendence crackled in the air. Concert-goers sought out what they called the numinous “X-factor”—that peak moment when all the energies of the Universe would flow through Jerry’s twanging guitar. These kids were higher than giraffe pussy, wilder than a retarded bull-rider, and smellier than a gully dwarf’s fuzzy butthole. It was like amazing, brah.

As the 80s rolled around, Garcia was disillusioned at best with this hippy horde, but they desperately needed him. Despite his increasing devotion to side projects such as The Jerry Garcia Band and his enduring compositions with longtime friend and mandolin-player David Grisman, Jerry was tied to his fans on a cosmic level. He would have to console himself with melting tubs of Häagen-Dazs ice cream and continuous smoking of pure China White heroin, but Jerry would not let the Deadheads down.

In 1986 Garcia overdosed on sugary snacky cakes and fell into a diabetic coma. It was to be a long strange trip, during which he encountered insectoid creatures on a galaxy-hopping starship. Jerry actually had to relearn to play the guitar when he landed back on Earth, but apparently he’d learned a little something about concocting a catchy hook while in space. The Grateful Dead released In the Dark the next year, which propelled the group to phenomenal popularity. “Touch of Grey” was featured on MTV and the album sold like fresh barrels of Orange Sunshine. To the horror of hardcore ‘heads, the lot scene was suddenly flooded with jocks, preppies, and corporate shills. The Dead’s show became a parody of itself overnight, and Jerry’s passion for his creation continued to dwindle as his bank account exploded.

Unfortunately, money couldn’t buy Garcia his health. Despite lumbering attempts at dieting and repeated stints in rehab, Jerry just couldn’t shake his snack-n-smack habits. His cup overflowed with love, as evidenced by his three wives, four daughters, and countless friends, but his fat-clogged heart strained to keep pumping the heroin to his frayed nerves. He continued to tour when his health permitted, but frequently forgot songs he’d played a million times in mid-strum. Fortunately, most fans were too fucked up to care, but their bootlegs survive to tell the tale.

Jerry’s last tour in the mid-90s was to be fraught with disaster. Once again, America was sick of its freeloading hippies. Numerous locales viewed Garcia’s vagrant masses with suspicion, and local police began responding to any sign of defiance with heavy clubs and pepper spray. Even oldschool Deadheads were put out with the more belligerent spirits among them. They began circulating flyers urging tie-dyed punters to “cool out,” stop breaking shit, and for God’s sake, pick up at least a few pieces of trash on your way out of town! Despite every attempt to save the scene, the Deadheads’ portable Utopia would soon come to an end.

On July 5, 1995, the chaos peaked at Deer Creek Amphitheater in Noblesville, IN, where anarchic fans lost all sense of nobility. Thousands of ticketless revellers amped up on feelings of unbridled freedom smashed through the venue’s fence, hurling planks and bottles at security. “Fuck you” was the watchword of the day, and skulls were cracked by both police batons and flying debris. The band was disgusted, cancelling the next night’s show and publishing an open letter to all Deadheads. The letter urged fans to dismantle their Lord of the Flies lot scene or else the band would stop touring. As it turned out, the death of the Dead hinged on Jerry’s indiscretions, not the unruly tribe he had attracted.

Jerry Garcia checked into the Betty Ford Clinic soon after the Deer Creek riot, but left after only two weeks. About a week after his fifty-third birthday, Jerry decided to give sobriety one more shot and checked into Serenity Knolls treatment center. A nurse found him dead of a heart attack on the morning of August 9, 1995. His continuous intake of drugs and grub had taken its toll, and Garcia joined his friend Janis Joplin and The Dead’s four “hot seat” keyboardists in the Great Jam Band in the Sky.

News of Garcia’s death hit devoted fans like an unshakable bad trip. Many gathered at 710 Ashbury—the birthplace of The Grateful Dead—to contribute flowers and photos to a growing memorial. Twenty-five thousand fans gathered at an official public memorial in Golden Gate Park on August 23rd, where the rainbow of tie-dye was darkened by a cloud of black armbands. Deadheads shed a million tears which, if collected, could probably dose an entire music festival for a weekend. As per his last will and testament, half of Jerry’s ashes were poured into India’s sacred Ganges River; the other half were emptied into the San Francisco Bay.

One fan asked the big question on everyone’s mind: “What happens to a community when its messiah, when its icon is gone?”

Typically, he is resurrected in one form or another. In the case of the Deadheads, many went on to follow Phish and Widespread Panic. Some retreated back into the ranks of the Rainbow Family where they continue to uphold the values of communal living off the larger social grid. Out in the wider world, Grateful Dead memorabilia continues to adorn music festival vendor stalls and college dorm rooms. The Internet has bestowed access to once-rare live bootlegs upon the initiated and the profane alike.

It has been over a decade and a half since Garcia’s passing, and yet one still occasionally sees an old VW bus covered in skeletons and teddy bears sputtering down the highway, chasing dreams of a world where universal love breaks the chains of human depravity. Who knows? Perhaps they will find it at the end of the psychedelic rainbow.

© 2011 Joseph Allen

The Grateful Dead — “Ripple“